Veteran French teacher shares his story

Seniors select Mr. Spurgin as their Commencement speaker

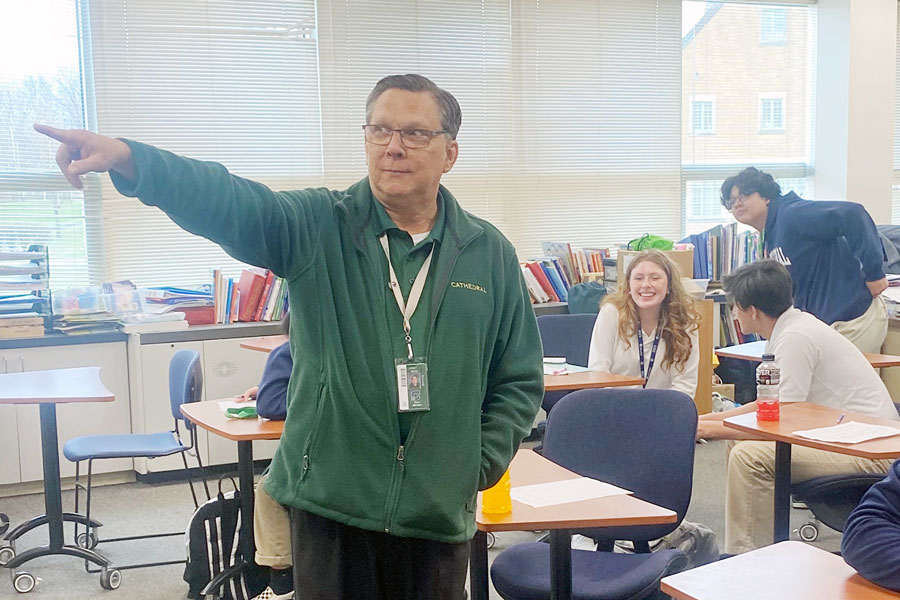

In his classroom, French teacher Mr. Gary Spurgin makes his point. As the faculty speaker at this year’s Commencement, Spurgin will have even more points to make.

“On the first day, I was there at Princeton (Community High School), eating lunch, when all of a sudden there was this huge crash. The teachers’ lunch area was (separate from) the students’ lunch area. Someone had decided to do wheelies in the courtyard, and because the cafeteria windows were all glass, (they) kind of got out of control and ran through the cafeteria. I thought, ‘I don’t want this.’”

French teacher Mr. Gary Spurgin spent the first six years of his teaching career at Cathedral. “During the early ’80s, Cathedral was not in great financial straits,” he said. “Everybody was saying, ‘You’ve got to get to a place where you have security as far as finances go,’ so I left one year, and I went to Princeton, Indiana, to teach. I did not like it, and one day I was visiting Cathedral because I still had friends here, and Fr. (Patrick) Kelly asked me if I’d like to come back. I said, ‘Sure, I’ll come back as a maintenance worker if you want me to.’”

Located north of Evansville along U.S. 41, the town of Princeton, Indiana, has a population of fewer than 9,000 people who live in an area that occupies five square miles. “(In Princeton) I was shocked at the students’ understanding of the world. I was teaching students who had never been to Indianapolis. (I was) trying to teach a world language (and) bring the world to them, but they didn’t understand their own state, let alone their own country. Did I have excellent students there? Sure, but only a handful,” he said.

“It was a stark contrast,” Spurgin continued, “going from a school (like Cathedral) where everything was academic to a school that was anyone and everyone.”

Cathedral has become renowned for its excellence in education, and this excellence has been one of two constants throughout Spurgin’s four-decade career. The other? Change.

“I know it’s in our brochures, but I have seen a huge commitment to a diverse student body. And when we talk about diversity, we’re talking about a range of diversity. We’re talking about socioeconomic, race (and) creed,” he said.

Spurgin also noted that as time has progressed, the school’s commitment to the welfare of its students has dramatically improved. “I think you have to live through it, and then after a while, you look back and, when you talk about educating hearts and minds, we have always done that. I think (now) we are more intent on providing a well-rounded education. I see a huge commitment to helping every student no matter where they are. I’ve never seen as many resources as we have (right now).”

One of those resources is technology. Every classroom has been outfitted with a projector and an Apple TV, allowing teachers to show electronic learning materials in class rather than dealing with physical classroom materials daily. “I used to hold pictures up,” Spurgin said. “Technology, I believe, has enhanced my teaching because I can bring the French-speaking world into the classroom, showing things that I was never able to before. Sharing resources with students that didn’t exist before.”

He also noted how technology’s integration into the 21st-century classroom has opened up a new world of flexibility. From being able to create worldview-altering lesson plans to making last-minute changes on the fly, it would seem like projectors, MacBooks and iPads offer nothing but benefits.

However, like any modern innovation, this technology has its drawbacks.

“(Teaching) is more challenging because (teachers) are up against students’ use of technology, but not in a right way. It’s a double-edged sword. It’s a constant struggle to make sure that students are using technology appropriately.”

Spurgin’s reasoning for this is all too familiar to many students: “A teacher says, ‘OK, we’re going to this website, and we’re going to do this great activity,’ you’re on your iPad doing what you’re supposed to be doing, and the kid next to you is playing Clash of Clans.”

An excellent place for students and teachers alike to disconnect from technology is their retreat. Spurgin has been a retreat leader on the Hill since the year of the renowned metal band Megadeth’s first album release: 1985.

After shadowing an adult leader, Spurgin said he was taken aback by how much the students had to give. “Being a student does not define you. There’s so much more,” he said.

“I love it. (Longtime, student-favorite retreat leader) Mrs. (Jacqueline) McNulty has always said, ‘I’m a retreat junkie.’ I think you can speak with a lot of educators here who are retreat junkies. For me, more than anything, retreat is a way that we are all able to share our faith journeys with others,” Spurgin said. He described retreat as a place where participants can be themselves. “Let’s put everything down: here’s who we really are. In real life, sometimes, we have to protect ourselves. Retreat is a way to have everyone share their spiritual journey.”

Not only has Spurgin experienced many spiritual journeys on retreat, but he has also made the trip across the pond to France between 40 and 50 times. Consequently, he has adopted many French mannerisms. “My actions, sometimes, are more French than American,” he said.

Spurgin said that he has observed the French as being more reserved than Americans. “You don’t get in their personal business the first time you meet (the French). Within three minutes, you could probably learn about Americans and everything about their lives: family, job, et cetera. For the French, it takes longer than that.”

During his many trips to France, Spurgin has had countless conversations with natives of the country, and he has observed a distinct difference in the dialogue between French people and American people.

“They’ll ask you, ‘What do you think about (any given issue?’ In French, you can be honest, and you still walk away being friends,” he said.

“In the United States, if someone was to ask me what I think about something, I always preface it with, ‘Do you want to know my opinion, or do you want me to agree with you?’ I think in the United States, we try to soften everything. I’m not saying I’m a hard-nosed person. This is why I say I’m more French. I call it the way I see it rather than sugar-coating it.”

Spurgin expanded upon this point, offering a hypothetical scenario that involves a bird pooping on the heads of two people and their differing reactions to the defecation situation, the specifics of which are not appropriate to publish in a student newspaper. Rest assured, he is not someone who sees things through rose-tinted glasses.

“Everybody’s walking on eggshells because we don’t want to hurt the other person’s feelings,” he said. “I get it. I’m not out to hurt your feelings, but if you ask me my opinion, do you want the truth, or do you want me to agree with you? I’ll go either way.”

Just as Spurgin’s social outlook can go in diverging directions, so too does the learning in his classroom. Not only do students learn from him, but, likewise, he garners more than his fair share of lessons from his pupils.

Spurgin offered three words as points of emphasis: Forgiveness, patience and inspiration. “People hold grudges,” he said. “Teachers are not always well-liked when they enforce rules or when they come down heavy on (students) for something, kind of like a parent would. When a student says, at the end, ‘We’re OK, we’re good.’ It’s not that you become best friends, but you know it’s good because you continue that relationship.”

One student who is well-versed in this dynamic is senior Chris Kiki. A student in Spurgin’s French I and II classes during his freshman and sophomore years, Kiki had rocky moments during his two years in the long-tenured teacher’s classroom.

“I was a good student grade-wise, but we used to butt heads a lot. But,” Kiki said, “he was always looking out for me and trying to keep me on task. He knew how good of a student I could be if I just focused. Most teachers obviously care about you, but they don’t go out of their way to show how much they care about you. He would always pull me to the side, whether it was before class or after class, and talk to me — just have conversations with me, really.”

Kiki learned the foundation of the French language in Spurgin’s class, but the most important thing he learned was always to carry a positive mindset. “The most important lesson (I learned) was, no matter your situation, be a good person,” Kiki said. “Spurgin’s not just a great teacher, but, more importantly, he’s a great person. He does his best to show that with all of his students, and he cares about his students and the school.”

So great is Spurgin’s compassion for his students and the school they share that he was voted by the Class of 2022 to speak at the Commencement ceremony on May 22. This will be Spurgin’s third time speaking at graduation: his two prior selections took place in 1994 and 2017, the latter of which was his son’s graduation.

“(Mrs. Katie Lewis) came to me (during the first week of April), and she asked me, ‘Do you accept?’ I didn’t respond ‘yes’ immediately. It is a daunting task,” Spurgin said. “All types of emotions go through your mind: excited, yet fearful because you’re going to be in front of maybe two thousand people. Am I worthy?”

Spurgin conversed with his wife, whom he married the same year as his first Commencement speech in ’94. She offered wisdom, saying that he has to trust the collective vote of the Senior Class. “I think you have to approach that honor with humility,” he said. “It is very humbling because what I truly believe (is) every educator here is worthy of that honor.”

When your career spans four decades, it can be challenging to quantify what kind of legacy you will leave behind. For Spurgin, it is two-fold. “I would hope students think and would say, ‘Mr. Spurgin is dedicated to helping us become our best and (wants) us to become lifelong learners.’ I believe in (lifelong learning). I’m going to take a class this summer. The second thing (is), I hope (students) would think that Mr. Spurgin is a humble teacher who was a faithful servant to his calling,” he said.

“For me, there have been times of doubt. When you run into certain obstacles, but then something occurs, and you think, ‘No, I love teaching.’”

“This will probably go on my epitaph: ‘He loved what he did. He taught to his fullest.’”

Nicholas Rodecap is a senior and co-editor-in-chief of the Megaphone. At Cathedral, he is a drum major in the Pride of the Irish marching band, a varsity...