Senior puts his tech skills to use for his school

Egan writes software intended to help students access classes

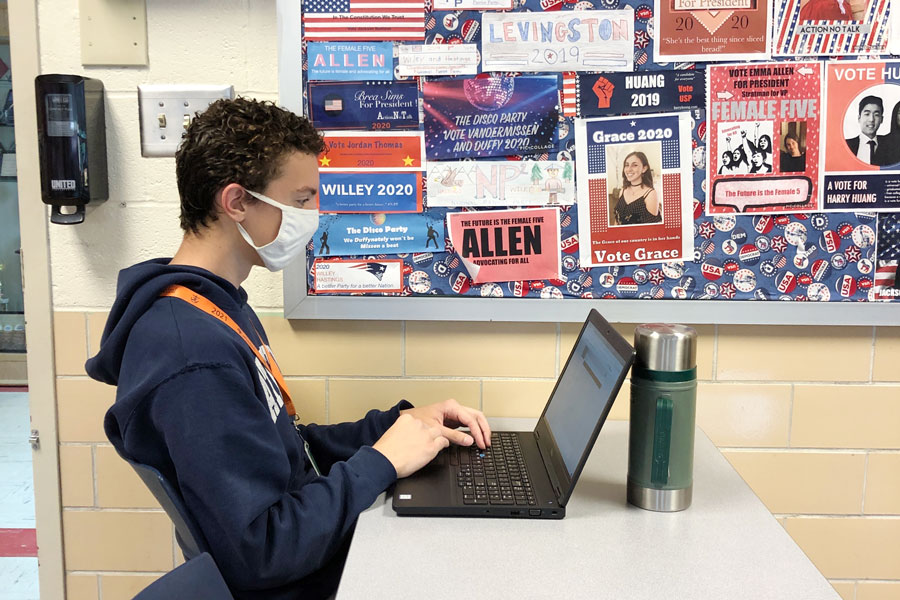

Senior Joe Egan wrote the software that students use to connect to classrooms.

The advent of radio at the turn of the 20th century spurred new ideas about how information could be distributed. News, from politics to sports to the latest Hollywood scandal, could reach all across the country.

One hope was that the traditional model of education could be updated with modern tools. No longer would learning be confined to a physical classroom, but instead a teacher could broadcast their lesson on the airwaves. A little over a century later, the traditional model is still the norm.

However, in the age of the coronavirus, it has become necessary to break from tradition. In the same way that early speculators hoped to broadcast education, senior Joe Egan has utilized his knowledge of computer systems to develop a way for students at home to continue their education.

EduStream is software that allows students to view a stream of their classroom through the placement of a camera in the classroom. Over the summer, Egan was on the Hill fixing some newly donated 3D printers, and was asked what he thought of the initial approach at virtual learning. The software that was going to be used had “a lot of costs and hassle,” said Egan. He hoped he could find a more streamlined option and began research.

The alternative became EduStream. Students must be registered as online, but then they can find their access information. Once logging in, students will automatically start viewing their class. During passing periods, no feed will show.

The software hasn’t had the smoothest of starts, however.

Challenges with EduStream have been “numerous and varied,” Egan said. The primary issue involves scaling, which is the ability of a system to handle continued use and growth. Initially, Egan prepared for the amount of students who declared that they would opt out of in-person classes with some room to grow for expected quarantining.

However, the rapid increase in online students — as of the end of August, more than 160 students, including numerous fall athletes, had signed up for online instruction — put immense strain on the system, and it didn’t scale as expected.

Senior Jake Wallmeier, who spent a week quarantining, said, “The first day that I used (EduStream), I didn’t really have any problems, but every day it’s gotten worse and worse. I would literally log in and it would just immediately send me back to the log-in screen. It would be really helpful if they got it to work because the graphics and sound are very high quality.”

Junior Kiersten Fisher wrote in an email that sometimes the software would cut out, but “it’s a diamond in the rough. I’m sure with some revision and tweaks, it can be everything our imaginations had desired,” she said.

Freshman Kristyn Fisher said in an email, “I feel like the teachers are trying really hard and giving their all to keep virtual learners as well as in-person students engaged — and I appreciate that. I enjoy the safety and comfortability of my home, and EduStream was a perfect canvas for that during the uncertain times of coronavirus.”

Audiovisual quality has fluctuated due to the increase in the amount of users. The week Wallmeier started quarantining, the amount of online students nearly doubled.

One common aspect students encounter is a delay of about 30 seconds. Egan explained that “the delay is a quirk of design. It wasn’t meant to be real time.” The software will record eight second chunks, send them to the server and the user requests them by viewing the stream.

Egan and the technology department decided that trying to have true live classes wasn’t as important, especially since trying to achieve instantaneous feed would be much heavier on the server and would likely slow everything down even more.

Egan said, “I have experience writing software, but not scaling it to serve hundreds of people.” Recent design shifts in the server’s architecture have been made to hopefully accommodate more students, but it will still be difficult. He said, “It was the kind of thing where you don’t know you don’t know something until you do, and now that I do, I’ve been working really hard on it.”

Egan said that recently he’s been able to work out some of the issues on paper, and is transitioning his findings over to code.

Egan’s computer background stretches way back. “It started with wanting to play Minecraft to play on a really bad computer and needing to write a script to get it to play off a USB drive.” Making use of the internet, Egan taught himself enough to start working on his own projects. “I wrote the kind of text games you would find in the early ‘80s, and a Mario clone, but then I got interested in web development.”

By the time he reached eighth grade, Egan said, “I had more or less completed the Egan home school curriculum,” and was focusing more on his own projects by reading, writing and watching videos about programming. “I was showing a lot of interest in the field,” he said.

At some point an uncle in the STEM field recommended to his parents that Egan attend classes at Ivy Tech so he could continue to learn and earn credit along the way. All together, Egan amassed about 30 credits which places him somewhere between a freshman and sophomore at Ivy Tech.

Even after deciding not to continue college classes as an upperclassman in high school, Egan said that it helped give some structure to his learning, and pushed him a bit beyond his comfort zone.

“I haven’t stopped learning, though. I’ve gone from copying other people’s code, to browsing forums to flipping through thousand page manuals. The stuff you do messing around on a computer can be fun,” Egan said.

Just as radio held the promise to change society at the turn of the century, Egan views computers with the same promises for entertainment and education. Egan said, “Tech permeates so many different aspects of our lives. It’s like being born at the beginning of the industrial revolution when steam engines were being built. It’s like that now, where tech is blossoming in every corner of the world. To be able to harness that power, in a non-maniacial way, is an empowering feeling.”

Andrew de las Alas is a senior and reporter for the Megaphone. He runs varsity cross-country, is co-captain of the speech and debate team and co-president...