Who Wrote That Essay?

New AI models spit out essays in seconds. What could that mean for writing assignments here on the Hill?

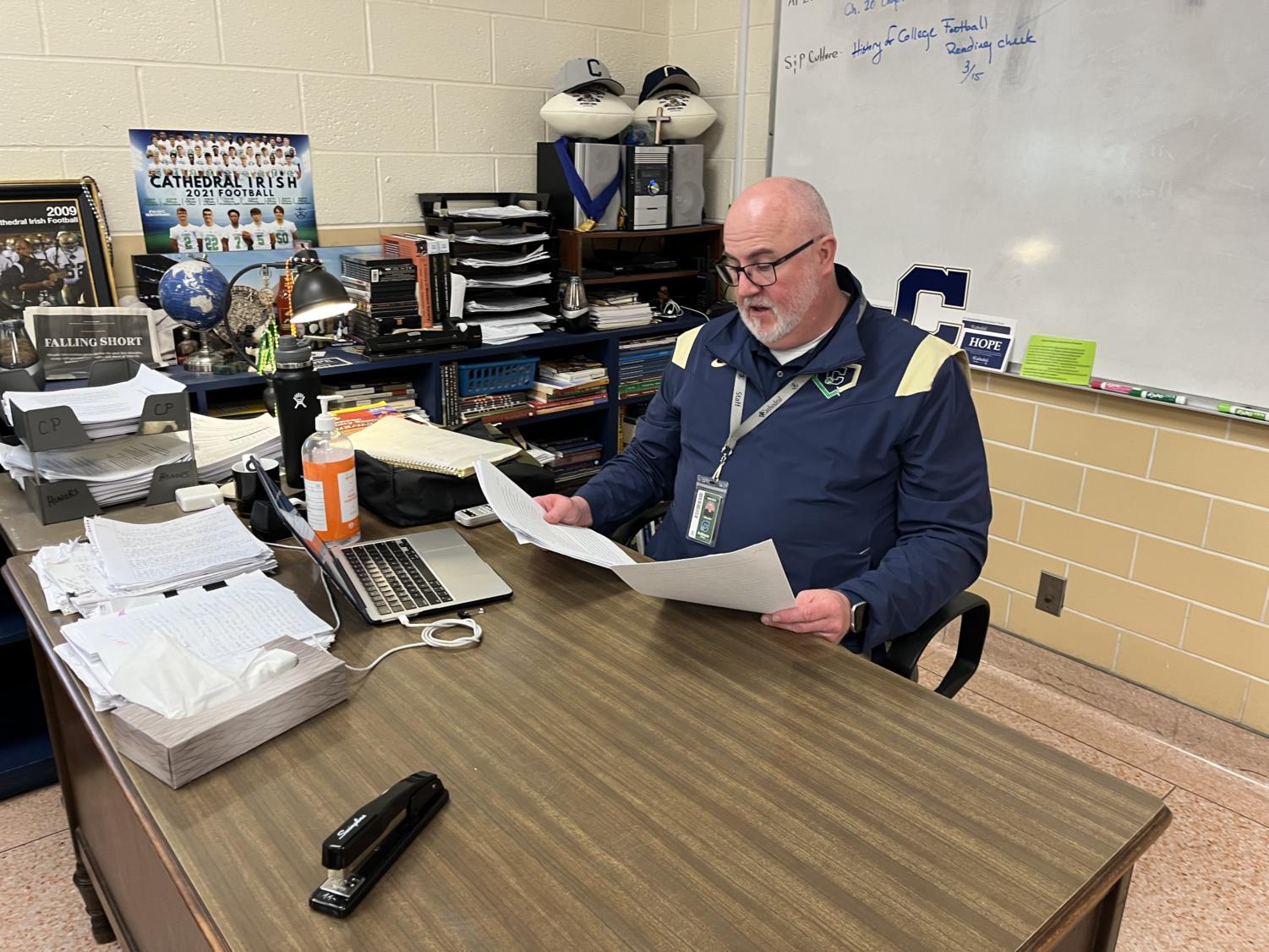

GPT3 is no Shakespeare. Director of Student Activities and History Teacher Mr. Anthony Ernst was given a sample AP Euro essay and one generated by the advanced neural network GPT3. Of the AI’s attempt, he said, “There’s no prose, there’s no flow to it. It’s choppy.” He was adamant that it did not come close to matching up with College Board’s top response, that it simply is not at that level. However, he quickly added, “What’s scary is it could be there.” Both Social Studies Teacher Mr. Jeffrey Darnold and English Teacher Mr. Matthew Panzer similarly deduced the AI generated response. Their comments will help evaluate the world of AI today, but perhaps it makes sense to first ask what this AI revolution might mean for students. Especially when it has grown in years, eloquence, and perhaps even deceptiveness.

Humanities Director Ms. Lizabeth Bradshaw has always been a bit of a luddite in regards to the age of iPhones and WiFi. She admitted as much herself, “I really guard against those things and my initial reaction is to shut things down and to take away and to go back to the old days.” Bradshaw frames the new challenge of AI in a similar manner to those posed by other technological advances. She said, “I mean the problem with this is the same problem with everything internet related. The easy quick answer is seductive and critical thinking, thinking for yourself, especially if the answers that you might be coming to might challenge what you want them to be, it’s hard for people, it’s hard for adults, it’s hard for kids, and so we all have to grow stronger character and a stronger why for what we do so that we don’t succumb to those things.”

As a philosophical point, Bradshaw’s advice makes sense. To some degree, students are just going to have to be wise enough not to cheat with AI. But, from a practical perspective, it would be foolish to only rely on the honor code. The solution might be more technological innovation in the form of some AI detector, like turnitin.com, but for robotic ghostwriters. Such programs already exist, many using the same AI networks to power them. OpenAI themselves, the creators of GPT3, released such a tool in late January, but claim it is a “work-in-progress.” Maybe it can get better than correctly identifying only 26 percent of AI text and incorrectly tagging 9 percent of human text as AI. Such a machine will always be imperfect though. The announcement of GPT3’s program concedes, “It is impossible to reliably detect all AI-written text.” And even if detectors get good enough for the current generation of AI, the whole situation can seem pliable to blow up into an arms race between AI writers and AI spotters. Ever better bots will need ever better bot-checkers as each tries to outdo the other. The future of innovation can feel like a hopeless spiral.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bradshaw looks to the past for grounding. She thinks the answer to the AI apocalypse might come in something Cathedral is already doing. In teacher-parlance, it’s called “visual thinking.” It’s in all the in between assignments that students have to turn in other than the final product. Rough drafts, outlines, and teacher meetings all give check-ins so that teachers can see the process that kids go through to craft their work. Through methods like this, Bradshaw hoped that Cathedral might help kids avoid the temptation to cheat. The problem, to her, is often more of bad teaching than advanced technology. She said, “If you send any kid off to do an essay that they feel is too difficult, that they feel is unfair, they don’t feel like they have the tools to do it, or they don’t have the time to do it, then they will seek a shortcut.”

For those worried about the moral integrity of Cathedral students, it should come as good news that while AI is certainly a capable writer, it’s still far off from getting a five on the AP World History exam by itself. Mr. Darnold, AP World teacher, said, “The AI was very succinct in their response. There was a lot of detail but there wasn’t a lot of analysis, there wasn’t a lot of contextualization.” He scored the AI’s Long Answer Question at only a three out of a maximum of six, lamenting, “The AI version was a little repetitive. The introduction and conclusion paragraphs were virtually the same.”

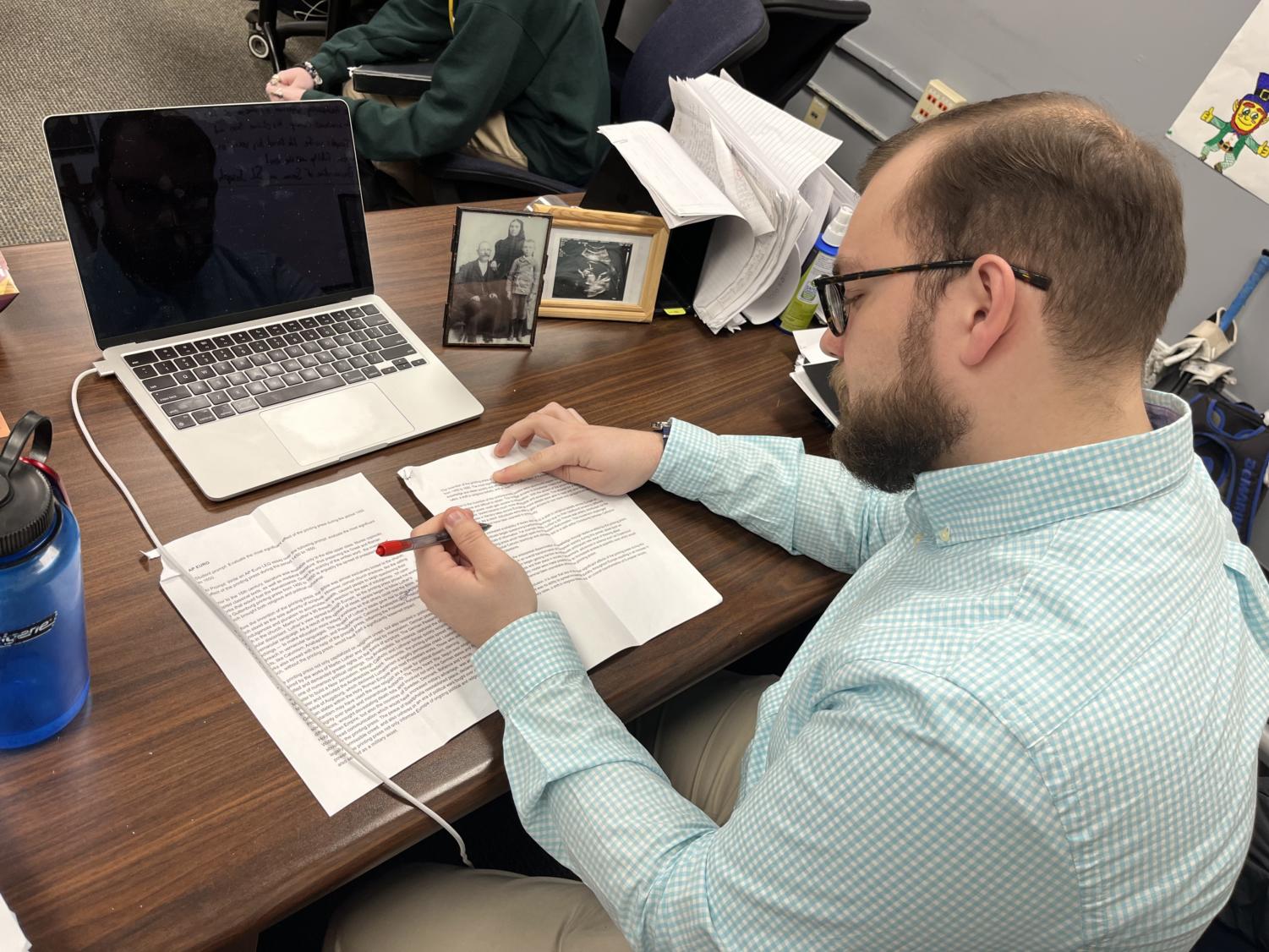

Of the AI’s attempt at an AP Literature Q3 essay (which aims to explain how a work of literature conforms to a given theme) Mr. Panzer said, “This is simplistic, but functional.” It didn’t meet the conventions of the form however. He said, “I’m looking for the hallmark of what should be taught in AP, and nowhere in the body paragraphs does it ever come back to (the author).” He claimed, “This is more of a summary. It’s accurate, but the highest it could get is a three.” He said of the AI’s performance on the essay, “If you do that three times, you’re not going to pass the exam.”

Panzer believed that AI may already be able to write convincing essays for lower grade level, non AP classes. He thought that an essay on The Great Gatsby, for example, might have more of a chance to pass. He said, “If that were a sophomore academic level class, yeah, I know what to expect.” About the senior year research paper required of AP Literature students, Panzer referenced some of that visual thinking Bradshaw mentioned. The need to annotate the book and submit an outline significantly lowers down the threat.

Panzer thought that AI might force teachers to tailor assignments so that they are meaningful work, not just busy work. The more routine, mundane, or formulaic the questions, the better AI will likely be able to answer them. He said, “(AI) is going to make us look at what we assign and how we value what we assign. And maybe that’s a good thing.” He preached a sort of form over function approach to writing. He said, “What you say should be kind of irrelevant unless you’re saying something incredibly stupid. Do you have the skill to incorporate evidence? And that’s what people like to see. ‘I understand the argument, I’m using the argument, and I’m explaining the argument.’ That’s high-level thinking.” AI could be a transformative force, forcing teachers to assign work that is unfakeable by being more personal, meaningful and, somewhat ironically, human.

Darnold had some ideas about how AI could be used as a more explicit tool in education too. He said, “I think there will be ways that students, especially in the high school and college level, can use this to their advantage. Not just to the point of them having a full length essay written, but they may use it as a tool to be like, ‘Hey, I’m going to put this prompt in and see if there are details it brings up that I might have forgotten.” And they can use it as an aid if they’re struggling to remember distinct information as an example.” Mr. Panzer drew on his time teaching students at North Central for whom English was not their first language. He said that by using the framework of an AI generated essay, those students might be able to add evidence and improve the essay in a way that would have been unachievable had they been forced to start from scratch.

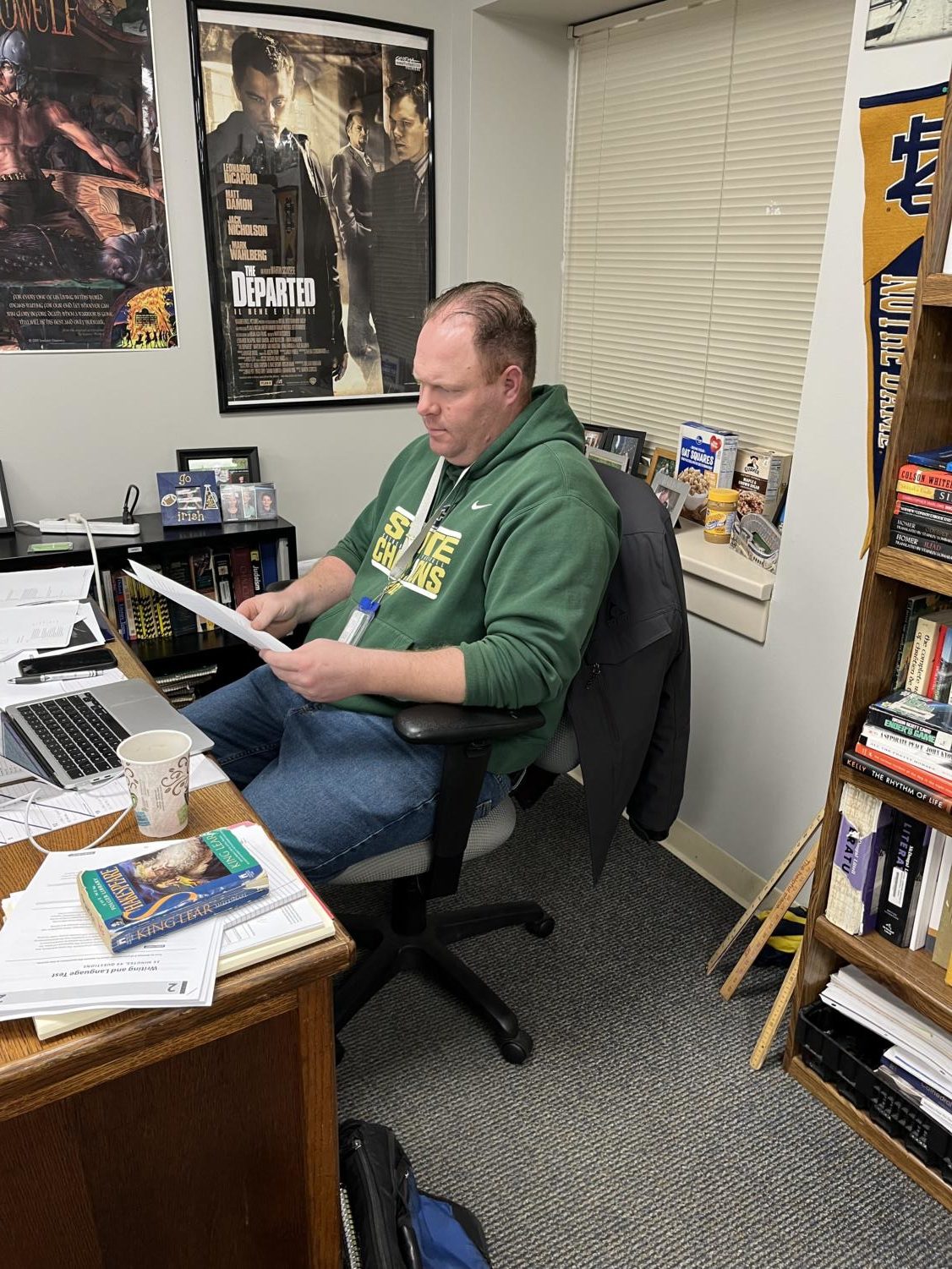

Still, Darnold at least wasn’t overly optimistic, claiming, “Right now, the downsides definitely outweigh the benefits because of how tempting it can be for kids to cheat with it.” He feared that AI might significantly change how he has to teach his AP World class. He said, “I can definitely see how within a few short years, I’m definitely going to have to adapt where there’s going to be fewer take-home essays in my AP World class.”

Though the implications of AI-generated essays are largely still unknown, it is clear that it has the potential to profoundly change the way teachers assign and grade work. AI could be used to help struggling students or used to cheat the system, depending on the intentions of the user. Ultimately, it is up to teachers, students, and administrators to ensure that the use of AI-generated essays does not become a way to game the system. It is possible that AI-generated essays could be a useful tool in the classroom, but only if there are measures in place to prevent cheating. With proper oversight and guidance, AI-generated essays may become a valuable aid in education.

Did that conclusion read a little funny to you? If not, you aren’t appreciating the painstakingly crafted prose of the author nearly enough because it took less than 3 minutes to login to GPT3 and ask it for that conclusion. I thought about asking it to write the whole article — deadlines are tight after all and it is a neat gimmick.

But that’s not why I do this. I write because I don’t really understand anything until I’ve got it down in words. Writing is as much an ordering of my own thoughts as it is a product to be consumed. Maybe, for that reason, the act of writing will be a thought crime against our AI overlords in thirty years’ time. In that case, I’m willing to fight this battle again. Robots might very well replace my work in thirty years, but I refuse to let it supplant my thoughts. Maybe Cathedral’s job isn’t so different. Maybe this, writing only because it might improve ourselves, is what it might mean to educate hearts and minds in the coming world of machines and algorithms.

Liam Eifert is a Senior and the Megaphone co-editor-in-chief. He runs cross-country and track for Cathedral. In his free time, he likes to read, study...